Cant and Johnstones complementing hypothesis that early reproductive cessation reflects “the ghost of

reproductive competition past” (Hrdy 2009 and Cant and Johnstone 2008) predicts

that there will be obvious costs to females that are breeding alongside a

reproductive grandmother. This hypothesis does

not imply that older females who have experienced menopause should not assist

daughters if the dispersal system becomes less female-biased or mothers are

able to maintain kin ties to their daughters.

Variation amongst individuals or

populations in factors that change the intensity or

timing of reproductive competition from the next generation is predicted to associate

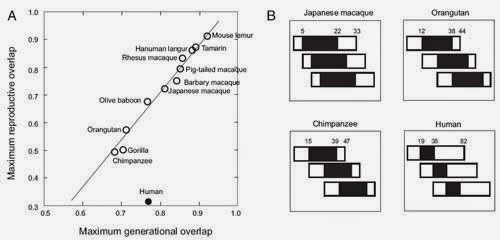

with the age at last reproduction as well as reproductive overlap. Social

system variation shown by modern humans also demonstrates the physiological

processes underlying the species-wide trait of rapid reproductive senescence (a cell that is no longer capable of dividing but still alive and metabolically active) compared with the possible flexibility of behavior that

leads to menopause.

The decision to help daughters outside the

family increases the relatedness asymmetry which favours younger females in

within-family conflict, as older females are able to help produce grand offspring

that are related by ¼.

However, assuming that parenthood uncertainty

is extensively accepted as a factor favouring maternal over paternal grand

mothering, it is helpful to compare the magnitude of this effect with the

magnitude of the relatedness asymmetry between older and younger females.

The

kin-selected benefits of helping can explain post reproductive survival, but

not why women cease reproduction so early in the first place. A model

incorporating reproductive competition can help to account for this trait and

for the particular timing of reproductive cessation in human females. Cant and

Johnstone suggest that a combined model that takes into account both the

inclusive fitness benefits of helping and the potential inclusive fitness costs

of reproduction suggestions an improved understanding of the evolution of

menopause.

References:

Hrdy, S.B. (2009). Will the Real Pleistocene Family Please Step Forward? Anon, Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding (pp. 207). United States of America: Anon.

Bereczkei, T., & Dunbar, R.I.M. (1997). Female-biased

reproductive strategies in a Hungarian Gypsy population. Proc R Soc London

Ser B 264:17–22

Johnstone, R.A., & Cant, M.A. (2008). Reproductive conflict and the

separation of reproductive generations in humans, 105(14):5332-5336.

Doi:10.1073/;pnas.0711911105.

Sear R., Mace R., & McGregor I.A. (2000). Maternal grandmothers improve

nutritional status and survival of children in rural Gambia. Proc R Soc

London Ser B 267:1641–1647

Voland E., & Beise J. (2002). Opposite

effects of maternal and paternal grandmothers on infant survival in rural

Krummhörn. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 52:435–443.